When I learned to fly – all those years ago – spin recovery training was a mandatory part of the PPL syllabus. Unless we could demonstrate fully developed spin recovery, left and right, with and without flap, we would not pass the PPL test – simple as that.

Our initial training was on Piper Colts, an aircraft that would just not spin – a spiral dive maybe, but not any kind of real spin. So to fulfil the syllabus, we were required to go spinning in an aeroplane called a Beagle Terrier – which, like its doggy namesake, displayed an interesting mix of mongrel and pedigree behaviours. The Terrier is at heart an Auster and like many 1940’s and 1950’s British aircraft, would bite you like a rabid dog, if provoked.

Every weekend, an RAF Wing Commander used to bring his little Terrier to the airfield for us very green students to go spin training. The procedure was to climb to 6,500 feet, do a few straight stalls and then start the spins. So, after clearing turns and carb heat to hot, we powered back to idle and slowly pulled back on the controls as the aircraft slowed down. Then, just as the nose started to drop in the stall, it was a time for a big bootful of right or left rudder and over we went. Wait for the WingCo to give the word and then opposite rudder to stop the spin and gently pull out of the dive, carb heat to cold and begin to apply power. The minimum number of turns in the spin before recovery action was three. Sometimes the WingCo went for four or even five turns before issuing the ‘stop’ order – always with a great big grin.

Learning spin recovery techniques was a bit scary at first – on occasion, the Terrier would go right over on its back and seemed to rotate about a point somewhere above (below?) your head and outside the plane – but as we gained in experience, all the students came to realise that knowing what to do in these circumstances improved our flying hugely and gave us more confidence to know we could handle at least some of the unusual flying attitudes which can occur in an aircraft.

Somewhere along the line, somebody in officialdom decided that it was either too dangerous to continue spin training or that it just wasn’t necessary with ever evolving safety in aircraft design – after all, even the old Colt couldn’t be provoked into anything like a real spin. Or both. Anyway, the training was changed to recognising potential spinning events and avoiding them. Or ‘incipient’ spin training. Which was probably a bad decision.

Recently, there has been a great deal of discussion and concern following an unfortunate incident in a certified aircraft conducting incipient spin training, as currently required per the CASA Part 61 Syllabus.

With it, there seems to be a lot of misunderstanding about the definition of what actually is an incipient spin, and it seems that even the local regulators have some difficulty defining it. Nevertheless, many (wrongly) assume the term to mean a stall with wing drop.

However, the generally accepted definition of an incipient spin is the transition phase during which a stall is propagating towards a developed spin – which, in some aircraft, may take up to two revolutions.

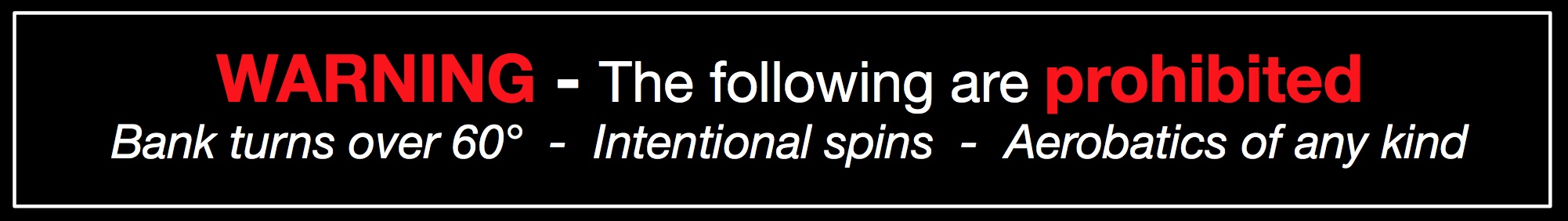

Remember that if the angle of bank exceeds 60 degrees or pitch exceeds 45 degrees from the horizontal, you are already outside of the allowable flight envelope of all LSA aircraft and therefore considered to be conducting ‘aerobatics’ under CASA’s definition.

Remember that if the angle of bank exceeds 60 degrees or pitch exceeds 45 degrees from the horizontal, you are already outside of the allowable flight envelope of all LSA aircraft and therefore considered to be conducting ‘aerobatics’ under CASA’s definition.

Here’s an extract from FAA AC 61-67 “Stall Spin Awareness Training”:

Here’s an extract from FAA AC 61-67 “Stall Spin Awareness Training”:

Normal category airplanes are not approved for the performance of aerobatic maneuvers, including spins, and are placarded against intentional spins. However, to provide a margin of safety when recovery from a stall is delayed, normal category airplanes are tested during certification and must be able to recover from a one turn spin or a 3-second spin, whichever takes longer, in not more than one additional turn with the controls used in the manner normally used for recovery, or [alternately] demonstrate the airplane’s resistance to spins.[ie you can’t spin it, whatever]

In addition, for airplanes demonstrating compliance with one turn or 3-second requirements, LSA requirements are:

– similar to the normal category but with less stringent requirements eg aggravated use of controls for FAR 23

– designed only for a margin of safety in delayed recovery from a stall. Therefore not intended for incipient spin training. [Remember, as above, an incipient spin is one which is recovered with the first 1-2 turns of the spin.]

While we are still awaiting a clearer definition from the regulator and would like to reiterate that no initial spinning is approved for the A22 or A32, the Aeroprakt factory does provide a declaration of conformity with the current Part 61 syllabus, with regard to incipient training, as follows:

![]() “Both A22LS and A32 were tested for spins. A special feature of the A22/A32 wing is such that during a classic method of spin entry when the pitch and yaw controls are deflected fully, simultaneously, the aircraft would not spin more than 180 degrees. After which the aircraft recovers from a spin to a steep spiral dive with increasing speed and normal acceleration (G-factor) in spite of the [continuing] fully deflected pitch and yaw controls.

“Both A22LS and A32 were tested for spins. A special feature of the A22/A32 wing is such that during a classic method of spin entry when the pitch and yaw controls are deflected fully, simultaneously, the aircraft would not spin more than 180 degrees. After which the aircraft recovers from a spin to a steep spiral dive with increasing speed and normal acceleration (G-factor) in spite of the [continuing] fully deflected pitch and yaw controls.

According to the ASTM (LSA) standard, an airplane may be used for spinning if the load factor and Vne are not reached by the end of the third spin turn.Taking into account the above mentioned, we cannot see any problem in permitting the use of our A22 and A32 aircraft for incipient spin recovery training as described in the CASA Part 61 syllabus, with the only limitation that not more than 1 spin turn may be done.” [11 June 2019].

In any case, at Foxbat Australia we recommend that any advance stalling and spin training should be conducted only in an aircraft certified for that purpose. There are many great flying schools around Australia which will allow you to receive proper spin instruction in a certified aircraft.

Whatever, if you like spinning, aerobatics, or neither(!) we highly recommended any pilot to learn more about them and experience them from the pilot seat.

STOP PRESS: CASA (Australian readers only) is seeking views on spin avoidance and recovery training. You can have your say by clicking the link below. NB> The survey closes on 27 January 2020.

https://consultation.casa.gov.au/regulatory-program/draft-ac-61-16-v1-0/

It’s an old debate. Personally, whatever the statistics say, I certainly FEEL much better about spins, incipient spins, out of balance stalls having now done full spins in a Decathlon. More relaxed about it probably means LESS likely to spin inadvertently I reckon.

The dynamics of spinning, for those interested, is discussed in some detail in the books of Mike Brookes (Empire Test Pilot School) called “Testing Times and “More Testing Times”. Reading your comment about the Terrier going “right over on it’s back” made me think of this: Brookes had to demonstrate that military aircraft were able to recover from inverted spins with aggressive “wrong” control inputs (into the spin aileron for an inverted spin for example). As well as being extremely disorientating, that must have been terrifying given that ejection was – to put it mildly – problematic under those circumstances.

Thanks Andrew – good comments

These updates are just part of Foxbat Australia’s excellent support. Thank you.

I went solo on Tiger Moths and spinning training was mandatory, later I was an instructor on Chipmunks and carried out numerous spinning sessions. Some students felt it was a dangerous exercise. However, I feel the hands, feet and senses were trained in an important art.

The modern cockpit is far more complicated than the the DH82 however the same basic principals apply. The use of Autopilot for most phases of a flight now masks the skills of hand flying with some current examples. just saying.