Probably the single most important factor in choosing an aircraft is safety – and it’s usually the most overlooked and under-rated aspect of an LSA.

Probably the single most important factor in choosing an aircraft is safety – and it’s usually the most overlooked and under-rated aspect of an LSA.

I remember (old geezer that I am) when motor car companies said that ‘safety doesn’t sell cars’ and they concentrated on looks, acceleration, top speed, road holding, even comfort. Volvo was just about the only company selling safety in their vehicles and as a result gained a reputation as a safety conscious, old people’s car, which has taken years to shake off. If they ever have.

Nowadays, all car manufacturers – not just Volvo – tell you how crash-resistant their vehicles are, how many airbags they have, how anti-skid the brakes and steering are. They have things like traction control and other electronic devices to get you out of the trouble your excess speed or other stupid behaviour just got you into.

So, what about Light Sport Aircraft safety? There are two main aspects to consider: primary and secondary safety. ‘Primary’ refers to the way the aircraft is designed to reduce the likelihood of an incident or accident happening in the first place. ‘Secondary’ refers to the aspects of the aircraft which reduce the effects of an incident or accident.

Aircraft primary safety can broadly be grouped into ground handling, take-off, stalling & spinning, and landing.

But first – ergonomics

But first – ergonomics

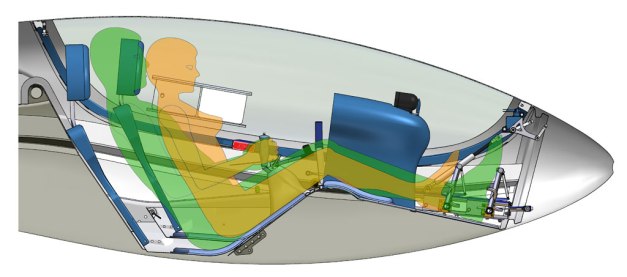

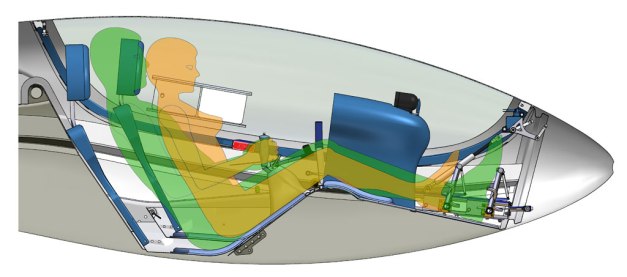

Ergonomics are a good place to start, because if they are wrong for you, it doesn’t really matter about the rest. Start with something completely counter-intuitive: how quick and easy is it to exit in an emergency like an engine fire? How easy is it to release the safety belt, open the door and hop out? Think: can I comfortably sit here for 2-3 hours and fly the aircraft? Are you cramped with a passenger on board? Can you still easily operate the controls to their limits with someone else next to you? If reaching a control, adjusting an instrument or even just looking outside the aircraft are a chore, these activities will soon be minimised and put in the ‘can’t be bothered’ basket and as a result, your safety will be compromised.

On the ground

Next, on the ground: how well does the aircraft steer and brake? It is well known that taildraggers are trickier to steer and brake than nose-draggers. But less well known is that some nose wheel aircraft can be a bit of a handful too.

Whereas most taildraggers steer via feet-operated differential main wheel brakes with castering (and sometimes steerable) tailwheels, most modern nose wheel aircraft steer more directly through rudder pedal couplings to the nose leg. This has the advantage of more directional control when the wheel is on the ground. But a potential disadvantage when landing in crosswinds, as the nose wheel may not be pointing in your direction of travel when it touches down.  This can lead to bent or even collapsed nose legs. So some aircraft designers have stuck with (or even reverted to) castering nose wheels, steered by main wheel differential braking – either by feet or hands. This gives slightly trickier ground handling especially when it’s windy but reduces the chances of bent gear when landing cross wind. Castering nose wheels usually have a smaller turning circle than direct steering, a particular advantage when back-tracking and turning on narrow runways. There are advocates of both systems – try both and take your choice.

This can lead to bent or even collapsed nose legs. So some aircraft designers have stuck with (or even reverted to) castering nose wheels, steered by main wheel differential braking – either by feet or hands. This gives slightly trickier ground handling especially when it’s windy but reduces the chances of bent gear when landing cross wind. Castering nose wheels usually have a smaller turning circle than direct steering, a particular advantage when back-tracking and turning on narrow runways. There are advocates of both systems – try both and take your choice.

In the air

First, take-off. When applying power for take-off, all single engined aircraft pull to one side due to the combined effects of gyroscopic forces from the engine and propeller and sometimes the spiralling airflow over the tail. Some aircraft have the engine offset so that it points to one side or the other to help minimise the pull – which can look a bit odd from some angles. Correcting the pull should be easy, through application of opposite rudder. However, some aircraft have a much stronger tendency to swing than others. Check out this effect and make sure it is controllable – particularly (eg) if the engine pulls to the left and the wind is blowing from the left, both of which will conspire to turn you off the runway if you don’t take prompt corrective action.

Stalling

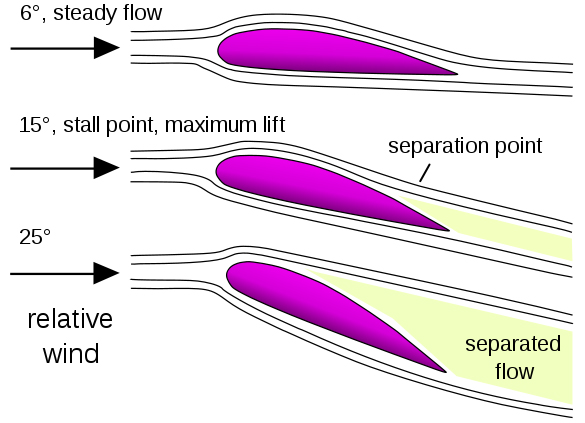

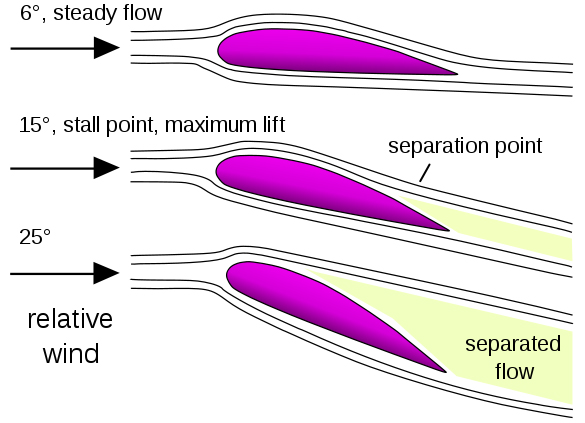

What about the stalling characteristics? Most LSAs stall very benignly, the nose goes down gently and rarely does a wing drop – something caused when one wing loses lift before the other, for a variety of reasons, but usually because the aircraft is being flown out of balance, with the slip ball not centred. Stalling with a wing drop is most dangerous when making that low-level turn onto final approach before landing. There are a few aircraft which can bite unexpectedly when stalled – if you are an experienced pilot and aware of what’s happening, prompt action can save you. But if the characteristic is particularly vicious and/or you are a low-time pilot, the chances are you won’t survive a finals turn stall with a wing drop. Check this aspect of the aircraft with someone familiar with the type and maybe even ask an instructor to take you up high and try stalling in turns.

What about the stalling characteristics? Most LSAs stall very benignly, the nose goes down gently and rarely does a wing drop – something caused when one wing loses lift before the other, for a variety of reasons, but usually because the aircraft is being flown out of balance, with the slip ball not centred. Stalling with a wing drop is most dangerous when making that low-level turn onto final approach before landing. There are a few aircraft which can bite unexpectedly when stalled – if you are an experienced pilot and aware of what’s happening, prompt action can save you. But if the characteristic is particularly vicious and/or you are a low-time pilot, the chances are you won’t survive a finals turn stall with a wing drop. Check this aspect of the aircraft with someone familiar with the type and maybe even ask an instructor to take you up high and try stalling in turns.

Now look at the relationship between stall speed and flap limiting speed. I know of at least one LSA where the stall speed without flap is less than 10 knots below the flap limiting speed. Think about it: you’re coming in to land and you can’t lower flap (eg) until 55 knots. Your stall speed without flap is 45 knots. So you don’t have much margin of speed in which to get the flaps down. Personally, I’d want an aircraft where the ‘clean’ stall speed is at least 40-50 knots below the flap limiting speed.

Spinning

Spinning is really just a stall with maintained wing drop. When I learned to fly, spin recovery was on the syllabus. The aircraft I started to learn on was a Piper Colt, which was difficult to spin – the best you could get out of it was really a spiral dive. To make sure we knew how to recover properly from a spin, we were all taken up in a Beagle Terrier – an excitable little aircraft whose bite was far worse than its bark! Nowadays you aren’t allowed intentionally to spin an LSA and spin recovery training has been replaced with ‘incipient spin’ recognition. Because unintentional spins almost always happen when the pilot’s attention is absorbed with something else, I personally believe spin recovery should be taught as part of basic training, even though most (but not all) LSAs are spin-resistant. At least you will learn instinctively to apply opposite rudder to stop the spin and then raise the nose and apply power. Check out how easy it is to spin your preferred LSA – the manufacturer is required to have carried out spin testing as part of the ASTM certification programme.

Landing

Approach speeds vary a lot with LSAs. Some require at least 65-70 knots down final, others as little as 40 knots. The faster the landing speed, the more wear and tear on the aircraft and the faster things happen if they go wrong. So in the same way you wouldn’t get into a Ferrari to learn to drive, so you shouldn’t get into a fast aircraft to learn to fly! Build your skills in slower gentler aircraft before taking on the trickier ones. And anyway, you might find you like going slow!

When assessing the aircraft’s landing characteristics, it’s important to check the correct approach speed – take it up to 3,000 feet AGL and try a few stalls. Note the indicated stall speed. Your approach speed for a low inertia aircraft like an LSA should be around 150% of that speed – much faster and you’ll float all the way down the runway; much slower and you risk a low-level stall. For example, the Foxbat indicated stall speed in landing configuration at maximum weight is in the low 30’s knots; approach speed therefore should ideally be around 50 knots. The factory manual actually says 49 knots. With one person and half fuel, stall in the Foxbat is around 26-27 knots – so approach speed can safely be reduced to 40-45 knots.

When assessing the aircraft’s landing characteristics, it’s important to check the correct approach speed – take it up to 3,000 feet AGL and try a few stalls. Note the indicated stall speed. Your approach speed for a low inertia aircraft like an LSA should be around 150% of that speed – much faster and you’ll float all the way down the runway; much slower and you risk a low-level stall. For example, the Foxbat indicated stall speed in landing configuration at maximum weight is in the low 30’s knots; approach speed therefore should ideally be around 50 knots. The factory manual actually says 49 knots. With one person and half fuel, stall in the Foxbat is around 26-27 knots – so approach speed can safely be reduced to 40-45 knots.

When landing, also look out for elevator authority. At least one LSA ‘runs out’ of elevator at landing speeds only slightly slower than its pilot manual advises. This can lead, at best, to a heavy landing; at worst to broken landing gear, because you can’t arrest the downward momentum without applying quite a lot of power. Usually, the reason the elevator loses its bite at slower speeds is because its travel has been limited so as to minimise the effects of inadvertent stalls – the downside is the loss of elevator authority when landing slowly.

In summary

Ground handling and flight characteristics of all aircraft are a compromise, based on what the designer/manufacturer is trying to achieve. Undoubtedly, current LSAs are among the safest handling aircraft available – after all, they mostly incorporate the latest computer-aided design techniques, they stall gently and are spin-resistant. But there are still a few mongrels among them.

Opinion about ‘pleasant’ and ‘unpleasant’ handling aircraft will always be divided so don’t rely on someone else’s personal preferences. Out there is an aircraft for you – fly as many different types as you can, if possible for at least an hour each. That way, you’ll begin to get the feel of the primary safety characteristics you like.

Next – secondary safety.

Aeroprakt has announced the release of a brand new aircraft in its range – the A32.

Aeroprakt has announced the release of a brand new aircraft in its range – the A32.

This is a non-fictional account of aviation in the 20th century, originally published in 1997. Allowing for the almost 20 years since its publication, this is an still an engrossing account of flying and aeroplanes – from the early pioneers like Saint-Exupéry and Markham and their lonely solo flights through to breaking the sound barrier with Chuck Yeager and many before, after and in between. Even including Biggles! It’s not a cheap book at over A$75 (if you can find a new one) but is completely absorbing and a marvellous compilation which you can dip into time and again and still find something new. Searching the usual book websites will turn up secondhand copies of varying qualities from as little as A$5 but make sure you know who you’re ordering from before leaping to buy!

This is a non-fictional account of aviation in the 20th century, originally published in 1997. Allowing for the almost 20 years since its publication, this is an still an engrossing account of flying and aeroplanes – from the early pioneers like Saint-Exupéry and Markham and their lonely solo flights through to breaking the sound barrier with Chuck Yeager and many before, after and in between. Even including Biggles! It’s not a cheap book at over A$75 (if you can find a new one) but is completely absorbing and a marvellous compilation which you can dip into time and again and still find something new. Searching the usual book websites will turn up secondhand copies of varying qualities from as little as A$5 but make sure you know who you’re ordering from before leaping to buy! Against a backdrop of flying the mail routes in the Sahara and South American Andes, Saint-Exupéry writes of friendship, death and heroism. The book describes his exploits and, in particular, his near fatal accident in the Sahara Desert, when he and his navigator/engineer almost died of thirst and dehydration after surviving the initial crash. The book was originally published in French in 1939 but was soon translated into English – and, shortly afterwards, significantly changed, as the author felt some of the content was not appropriate for its USA readers. In French, the book was titled ‘Terre des hommes’ (‘Land of men’) with the English ‘Wind, Sand and Stars’ suggested by the translator. Although the translation is many years old, the book is still a good read, telling of times when aviation was still an extremely risky business.

Against a backdrop of flying the mail routes in the Sahara and South American Andes, Saint-Exupéry writes of friendship, death and heroism. The book describes his exploits and, in particular, his near fatal accident in the Sahara Desert, when he and his navigator/engineer almost died of thirst and dehydration after surviving the initial crash. The book was originally published in French in 1939 but was soon translated into English – and, shortly afterwards, significantly changed, as the author felt some of the content was not appropriate for its USA readers. In French, the book was titled ‘Terre des hommes’ (‘Land of men’) with the English ‘Wind, Sand and Stars’ suggested by the translator. Although the translation is many years old, the book is still a good read, telling of times when aviation was still an extremely risky business. Another non-fictional account of flying across the USA in a small aeroplane – this time a 1950 Luscombe Silvaire (registered Zero 3 Bravo of the title), which, to the uninitiated, is a 2-seat metal high wing aircraft with a cruise speed of about 85 knots. This is the true story of 60 years-old Mariana Gosnell, who set out in the early 1990’s for a three-month trip from New York across the USA to the west coast and then back again. It recounts her experiences of the people she met along the way and is well-illustrated with photos she took. It’s one of those books that are very enjoyable and easy to read – the only downside (if you’d call it that) is that it will start you dreaming of (even planning) your own trip! Highly recommended.

Another non-fictional account of flying across the USA in a small aeroplane – this time a 1950 Luscombe Silvaire (registered Zero 3 Bravo of the title), which, to the uninitiated, is a 2-seat metal high wing aircraft with a cruise speed of about 85 knots. This is the true story of 60 years-old Mariana Gosnell, who set out in the early 1990’s for a three-month trip from New York across the USA to the west coast and then back again. It recounts her experiences of the people she met along the way and is well-illustrated with photos she took. It’s one of those books that are very enjoyable and easy to read – the only downside (if you’d call it that) is that it will start you dreaming of (even planning) your own trip! Highly recommended. I suppose no collection of aviation books would be complete without the amazing tale of the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean in a single-engined aeroplane. This is the book, written by Lindbergh, which was published many years – in fact over 25 years – after his epic flight. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1954, the year after its publication. Apart from covering the flight itself, the book also describes in detail the preparation and planning for the flight and, in particular, overcoming the almost insurmountable problem of building an aircraft with enough speed, yet still able to carry a pilot and enough fuel for the journey. In the end, the aeroplane was filled with over 450 US gallons of fuel (that’s over 1,700 litres) and just about managed to take off at almost half a ton overweight – that’s a lot for a small single engine plane. How Lindbergh stayed awake during his long solitary night flight towards Europe is recounted so well, you could almost be there yourself. New copies of the book can still be found with a little digging – it was reprinted at least in 2003. Here’s a link to s short video, with subtitled commentary on the take off:

I suppose no collection of aviation books would be complete without the amazing tale of the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean in a single-engined aeroplane. This is the book, written by Lindbergh, which was published many years – in fact over 25 years – after his epic flight. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1954, the year after its publication. Apart from covering the flight itself, the book also describes in detail the preparation and planning for the flight and, in particular, overcoming the almost insurmountable problem of building an aircraft with enough speed, yet still able to carry a pilot and enough fuel for the journey. In the end, the aeroplane was filled with over 450 US gallons of fuel (that’s over 1,700 litres) and just about managed to take off at almost half a ton overweight – that’s a lot for a small single engine plane. How Lindbergh stayed awake during his long solitary night flight towards Europe is recounted so well, you could almost be there yourself. New copies of the book can still be found with a little digging – it was reprinted at least in 2003. Here’s a link to s short video, with subtitled commentary on the take off:  Last but not least is this funny, charming, part fiction, part autobiographical tale, of a young man and his friend (only one of whom knew how to fly) who decide that owning an aircraft will make them chick magnets (his words, not mine). So they set out to buy a microlight/ultralight in the form of a tube, fabric and wire ‘Thruster’ aircraft – described as a flying lawn mower with two plastic chairs. Along the way, he learns about and makes lists of all the various microlighting paraphernalia and in particular, falls in love – not with a lovely young damsel – but with being up in the air and the sheer joy of flight. Captivatingly amateur in its approach, this is at the root of the book’s appeal, along with all the views of the world common to young men. In a way, it’s a ‘coming of age’ story which is well-told and, in parts, hilarious along the way.

Last but not least is this funny, charming, part fiction, part autobiographical tale, of a young man and his friend (only one of whom knew how to fly) who decide that owning an aircraft will make them chick magnets (his words, not mine). So they set out to buy a microlight/ultralight in the form of a tube, fabric and wire ‘Thruster’ aircraft – described as a flying lawn mower with two plastic chairs. Along the way, he learns about and makes lists of all the various microlighting paraphernalia and in particular, falls in love – not with a lovely young damsel – but with being up in the air and the sheer joy of flight. Captivatingly amateur in its approach, this is at the root of the book’s appeal, along with all the views of the world common to young men. In a way, it’s a ‘coming of age’ story which is well-told and, in parts, hilarious along the way.

When customers ask me about the Foxbat, the question I hear most is not ‘How fast?’, ‘How far?’ or ‘How much?’ but ‘What makes your Foxbat better than any other (or sometimes a specific) recreational/light sport aircraft?’ While I understand the reason for asking the question, it’s a bit like asking which is better: a pick-up/ute, a sports car or a sedan.

When customers ask me about the Foxbat, the question I hear most is not ‘How fast?’, ‘How far?’ or ‘How much?’ but ‘What makes your Foxbat better than any other (or sometimes a specific) recreational/light sport aircraft?’ While I understand the reason for asking the question, it’s a bit like asking which is better: a pick-up/ute, a sports car or a sedan.

For example – a farmer/landowner wants a strong landing gear and good safe slow speed handling so they can take-off and land in small spaces on unprepared paddocks. Outright top speed is likely not a key decider. The aircraft needs to be robust and reliable, because it’s going to be used a lot, and down-time is potentially lost money. And it probably needs to be easy and safe to fly near to the ground. And quick and easy to fix if it breaks down or gets broken.

For example – a farmer/landowner wants a strong landing gear and good safe slow speed handling so they can take-off and land in small spaces on unprepared paddocks. Outright top speed is likely not a key decider. The aircraft needs to be robust and reliable, because it’s going to be used a lot, and down-time is potentially lost money. And it probably needs to be easy and safe to fly near to the ground. And quick and easy to fix if it breaks down or gets broken. Another example: if you are a big person, you’ll need to be able to fit into the cabin – it’s a good job the Millennium Falcon had a roomy flight deck! And if you are heavy, you’ll need an aircraft that can carry you, a reasonable amount of fuel and probably a passenger. There are light sport aircraft on the market that can legally carry less than 200 kilos – that’s everything: pilot, passenger, baggage and fuel. Put two 90 kilo people on board, no bags, and that leaves you 20 kilos for fuel – about 28 litres, which will last about 75 minutes.

Another example: if you are a big person, you’ll need to be able to fit into the cabin – it’s a good job the Millennium Falcon had a roomy flight deck! And if you are heavy, you’ll need an aircraft that can carry you, a reasonable amount of fuel and probably a passenger. There are light sport aircraft on the market that can legally carry less than 200 kilos – that’s everything: pilot, passenger, baggage and fuel. Put two 90 kilo people on board, no bags, and that leaves you 20 kilos for fuel – about 28 litres, which will last about 75 minutes. Then there are the speed freaks – as long as they can say it goes faster than yours, it’s the one for them. But to go fast in an aeroplane demands compromises – smaller cabins, so there’s less drag; landings are potentially faster, longer and trickier; and the airframe has to be stronger (read: heavier) to cope with rough air at higher speeds…reducing the load carrying capacity. As one famous old American flying ace commented: ‘Unless you’re going at least 50% faster than the others, after a very short time you won’t notice any difference’. And next month someone else will buy one just a bit faster.

Then there are the speed freaks – as long as they can say it goes faster than yours, it’s the one for them. But to go fast in an aeroplane demands compromises – smaller cabins, so there’s less drag; landings are potentially faster, longer and trickier; and the airframe has to be stronger (read: heavier) to cope with rough air at higher speeds…reducing the load carrying capacity. As one famous old American flying ace commented: ‘Unless you’re going at least 50% faster than the others, after a very short time you won’t notice any difference’. And next month someone else will buy one just a bit faster. So an important thing to think about, when deciding which aircraft, is what’s best for you – and be realistic! How often will you really fly it? Will you usually take a passenger with you or fly alone? How far will you really go on a typical flight? Are you really going to fly round Australia in it, one day? Will the aircraft really carry the weight you need it to? Why is speed important? Is getting there 10 minutes quicker, probably using more fuel, really that important?

So an important thing to think about, when deciding which aircraft, is what’s best for you – and be realistic! How often will you really fly it? Will you usually take a passenger with you or fly alone? How far will you really go on a typical flight? Are you really going to fly round Australia in it, one day? Will the aircraft really carry the weight you need it to? Why is speed important? Is getting there 10 minutes quicker, probably using more fuel, really that important?

Probably the single most important factor in choosing an aircraft is safety – and it’s usually the most overlooked and under-rated aspect of an LSA.

Probably the single most important factor in choosing an aircraft is safety – and it’s usually the most overlooked and under-rated aspect of an LSA. But first – ergonomics

But first – ergonomics This can lead to bent or even collapsed nose legs. So some aircraft designers have stuck with (or even reverted to) castering nose wheels, steered by main wheel differential braking – either by feet or hands. This gives slightly trickier ground handling especially when it’s windy but reduces the chances of bent gear when landing cross wind. Castering nose wheels usually have a smaller turning circle than direct steering, a particular advantage when back-tracking and turning on narrow runways. There are advocates of both systems – try both and take your choice.

This can lead to bent or even collapsed nose legs. So some aircraft designers have stuck with (or even reverted to) castering nose wheels, steered by main wheel differential braking – either by feet or hands. This gives slightly trickier ground handling especially when it’s windy but reduces the chances of bent gear when landing cross wind. Castering nose wheels usually have a smaller turning circle than direct steering, a particular advantage when back-tracking and turning on narrow runways. There are advocates of both systems – try both and take your choice. What about the stalling characteristics? Most LSAs stall very benignly, the nose goes down gently and rarely does a wing drop – something caused when one wing loses lift before the other, for a variety of reasons, but usually because the aircraft is being flown out of balance, with the slip ball not centred. Stalling with a wing drop is most dangerous when making that low-level turn onto final approach before landing. There are a few aircraft which can bite unexpectedly when stalled – if you are an experienced pilot and aware of what’s happening, prompt action can save you. But if the characteristic is particularly vicious and/or you are a low-time pilot, the chances are you won’t survive a finals turn stall with a wing drop. Check this aspect of the aircraft with someone familiar with the type and maybe even ask an instructor to take you up high and try stalling in turns.

What about the stalling characteristics? Most LSAs stall very benignly, the nose goes down gently and rarely does a wing drop – something caused when one wing loses lift before the other, for a variety of reasons, but usually because the aircraft is being flown out of balance, with the slip ball not centred. Stalling with a wing drop is most dangerous when making that low-level turn onto final approach before landing. There are a few aircraft which can bite unexpectedly when stalled – if you are an experienced pilot and aware of what’s happening, prompt action can save you. But if the characteristic is particularly vicious and/or you are a low-time pilot, the chances are you won’t survive a finals turn stall with a wing drop. Check this aspect of the aircraft with someone familiar with the type and maybe even ask an instructor to take you up high and try stalling in turns.