Friday 5 September was taken up with a visit to the centre of Kiev, as well as a tour round the factory, a visit to the Aeroprakt airfield, just outside Kiev, and of course business discussions, questions and answers. Our host was Alexei Zhurba, one of the senior people at Aeroprakt, who speaks excellent English.

First though, Kiev is a beautiful city, made even more attractive by the late summer sunshine and 23-24 degree temperatures. There are tree lined streets and stunning architecture, much like many other European cities. We visited the ‘Maidan’, the square where all the unrest and fighting took place earlier this year. I found it almost impossible to imagine what happened here such a short while ago, although the seemingly endless memorial shrines to those who died are a shocking reminder. The city is now calm and the square has been largely cleared and repaired. All I can say is that those of us who have lived all our lives in the relative peace and security of Australia, and other westernised countries, are very lucky indeed.

Onward to the Aeroprakt factory, where it is very much business as usual. We met with several people, including Yuriy Yakovlyev, the CEO and A22 designer, Oleg Litovchenko, his business partner, and Nina, the sales and distributor liaison person. I have posted some more factory pictures in the Foxbat Pilot Flickr photo album.

Late in the afternoon we arrived at the airfield and were lucky enough to catch a few circuits in one of the Club A22LS aircraft, under the watchful eye of right-seat pilot Yuriy.

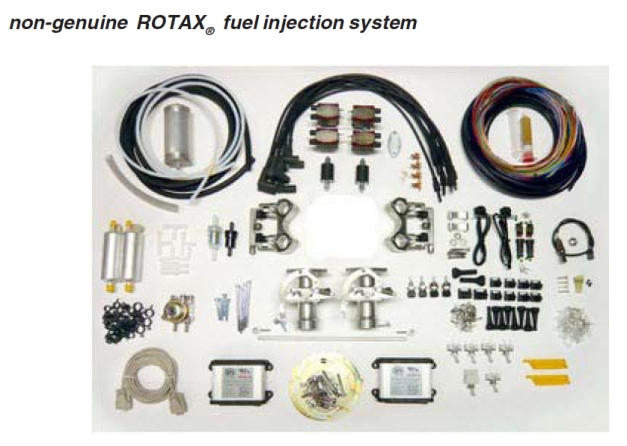

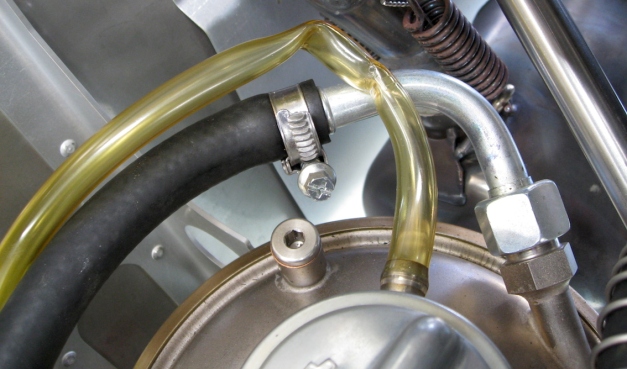

There is much more to report, including the availability of the 912iS Sport engine in new A22LS aircraft, a retro-fit engine mount and cowling to enable earlier 912iS engines to be upgraded to the higher spec 912iS Sport for Foxbats already delivered, a potential external power supply socket, a different tyre & tube option, and much more.

I’m aiming to cover as many of these as I can in future posts…so watch this space!

Saturday, we are hoping to get in some more flying at the airfield and expect to meet some more Aeroprakt people in a more social setting.