This one is a bit long, but well worth reading through to the 10 tips at the end. Thanks to Peter Kelsey for the words.

Wing Commander Ken Wallis (courtesy Gary Brown)

None of us is as young as we were and those of us distinctly nearer to the cemetery than the crib may be less competent pilots than we once were.

Greater experience and good currency may serve to compensate adequately for poorer reaction times and worsening cognitive skills but there will come a time when the sensible thing is to accept that continuing to fly as Pilot In Command (PIC) is risky and foolish. Continue by all means with someone else as PIC if you like but continuing in command and putting yourself, your passengers, your friends and your family at risk of a catastrophe because of your refusal to recognise the significantly reduced state of your abilities may be folly. When is the right time and what can you do to postpone it?

When should you stop?

26 years of age was generally regarded as the maximum for a new pilot to join an RAF fighter squadron during World War II. Beyond that watershed the poor old chap would probably not have quick enough reactions to survive although experienced fighter pilots of greater age could counter their slower reaction times with better anticipation.

55 is regarded by many as signalling another stage at which Commercial Air Transport (CAT) and General Aviation (GA) pilots should start asking themselves whether they are still able to hack it as well as they used to. 60 was often the compulsory retirement age for airline pilots until they were more recently allowed to continue to 65 provided that the other pilot in a two person crew was less than 60. This extension made no difference to accident rates. Nonetheless, somewhere around the 55 to 65 years stage pilots need to accept that, much like the engine on a certified aircraft, they have passed their TBO and further use must depend upon condition.

Insurers of GA aircraft have concerns about elderly pilots, especially those past 80 and/or flying only a few hours each year. On the other hand, in Air Facts (a US publication) Opinion of October 2011, Bob Claymore, Executive Vice President of United Flying Octogenarians, writes, unsurprisingly, under the heading: Older Pilots are Safe Pilots. However, he does accentuate the importance of diet and exercise if you want to continue in good working order.

Originally built in 1934 and fitted with a new fuselage in 1938 after a mishap on landing, this DH.83 Fox Moth is still flying. It is kept serviceable by careful maintenance and tender loving care.

Recreational pilots have no retirement age and on the face of it they can go on for ever if they can pass their periodic medical and the flight with an instructor. As for the medical, even the EASA Class 1 level concentrates mostly on the physical rather than the mental. Answering the questions about your own and your parents’ mental problems, your weekly consumption of alcohol, when you gave up smoking and then managing to write out the cheque are not that searching an investigation of your cognitive skills under stress.

So there remains a cohort of GA pilots who have made it through the various filters and are ‘legal’. Some of these may find themselves and/or their families still wondering whether the time has yet come to hang up the headset. And some may be attracted to Abelard’s prayer, Give me chastity O Lord – but not yet. The issue becomes increasingly important as the proportion of elderly pilots within the aviation community increases year upon year. This is partly the consequence of the ever increasing expectation of life and better health amongst the elderly and partly less availability of spare time from work and family commitments among those of working age.

Having researched the views of various authorities I can tell you that the question of continuing flying into old age is complex, involving numerous factors, many incapable of even approximate quantification. It is clear that at some time after age 55 competence will have fallen off to such a degree that it is no longer sensible to keep flying as PIC. For some that age will be early and for others late. I can recall interviewing at his home in Norfolk Ken Wallis, inventor and builder of the Wallis autogyro amongst many other creations. Accurately described as a cross between Biggles and Professor Branestawm he was at the time, in his early nineties, incensed at the CAA for withdrawing his display licence. In a hangar at the back of the house he kept his ‘harem’ of 16 or so autogyros and he would regularly wheel one of them out to take off from the parkland that surrounded his house. One of the harem, Little Nellie, had featured in the Bond film You Only Live Twice with Ken as stunt pilot. He considered himself, and probably was, entirely capable of continuing to display at local fetes but now the CAA were putting a stop to his charitable fund raising. My sympathies were with the CAA official, unwilling to risk a summons to the top floor of Aviation House in the event of an incident and an outraged reaction in the Press. Ken continued to fly regularly until nearer his death at the age of 97.

Elderly drivers

Elderly pilot issues are very similar to elderly driver issues. Indeed when it comes to the chances of causing death or injury to a third party the inadequate car driver must present an enormously greater risk to the general public than the inadequate private pilot. While analyses of accidents involving elderly pilots are few and far between, the much greater database of road accidents is a valuable source of statistical evidence.

To quote from Older drivers: An RAC Foundation perspective:

How safe are older drivers?

‘The car is undoubtedly important for facilitating mobility in old age, but there are often concerns about the safety of older drivers behind the wheel. In fact, today’s older drivers are no less safe than their middle age counterparts. The misconception

that the elderly are dangerous when behind the wheel is a function of their overrepresentation in the casualty statistics – older

motorists do not tend to have more accidents but their frailty means that they are more likely to be seriously hurt or killed when they do.

Until the age of 80, older drivers are only at greater risk of injury for every mile driven because frailty increases with age. It is only when drivers are over the age of 80 and/or travel less than about 2,000 miles a year that there is any type of increased risk due to driving ability. There may be an increased risk for drivers with certain illnesses although the effect of conditions such as progressive dementia has yet to be conclusively proved.’

While driving is not the same thing as flying it does call for similar skills and it is reasonable to expect corresponding similitude in the loss of a competence that was once taken for granted.

What are the particular problems associated with elderly pilots?

The Air Safety Foundation of AOPA USA has considered a substantial body of American literature on this subject and summarised this in a useful report: ‘Aging and the GA pilot’. Search for the report under its title. Page no’s from the report are shown against quotes below. Refer to the Selected Resources section at pp 25 to 39 of the report for the sources of quotations in this article.

However, even within the much larger US GA scene there is a shortage of hard information about the competence of elderly pilots. Nonetheless, accident statistics have been analysed and tests in simulators carried out. The report quotes from a research paper by Pamela Tsang as follows (p 11):

“The psychological literature shows definite age-related changes in certain cognitive functions that have been identified to be essential for flight performance (e.g., perceptual processing, certain aspects of memory performance, and certain psychomotor control). The cognitive functions that do not yet exhibit clear effects of age tend to be the more complex ones that involve several stages of information processing such as problem solving, decision making, and time-sharing. On the one hand, there are ample data to suggest that the more complex the performance, the larger the age effect tends to be. On the other hand, complex performance developed through extensive training is found to be more resistant to negative age effects. Since expertise in many complex job performances, including flying, tend to develop with experience and age, the interactive effects of age and experience and their relative contributions need to be carefully studied.”

A salient problem is radio communication. This may result from failing short term memory or maybe loss of hearing when stressed is the cause. Radio communication is the area in which aging itself has the most obvious and measurable impact (p 12). This suggests that inadequate R/T may serve as an early warning of failing flying competence.

The report summarises the big picture as follows (p 13):

… different pilots experience the aging process differently, and compensate for it (or fail to) in a variety of different ways. There are, no doubt, certain commonalities among older pilots, but in the broad view it seems that individual factors—experience, proficiency, physical fitness, genetics—come together to play a much greater role than chronological age in determining a given pilot’s ability to fly safely on a given day.

The report also quotes from a research paper prepared by Richard Golaszewski for the FAA and others in 1983 on The influence of total flight time, recent flight time and age on pilot accident rates. “… For low values of recent flight times, older pilots exhibit higher accident rates. … Accident rates increase with age when recent flight time is less than 50 hours per year.”

Here are some steps that you might take to keep flying safely into old age:

1. Fly frequently or not at all.

2. Physical health is crucial. Diet and exercise are all important here.

3. Note the gist of every instruction/clearance from Air Traffic before reading it back. When, two minutes later, you cannot recall what the precise altitude limitation was your note will tell you.

4. Fatigue is an increasing pitfall for the ageing pilot. Recognise that you cannot competently do as much you used to do five or ten years ago and limit your hours per day accordingly.

5. Cut out the more demanding sorts of flying – fly a simpler aircraft (after good type conversion training) – give up night flying and flying in marginal weather.

6. Use ATC and radar more. Accept that you are more prone to wander stupidly without a clearance into controlled airspace than you used to be. Get a Traffic Service and the extra protection from doing something stupid that this will provide. Failing that a Listening Squawk will be better than nothing.

7. Carry a Personal Collision Avoidance System (PCAS) or other electronic proximity warning device. Your eyesight is not as good as it was.

8. Get a noise cancelling headset. Your hearing is not what it was either.

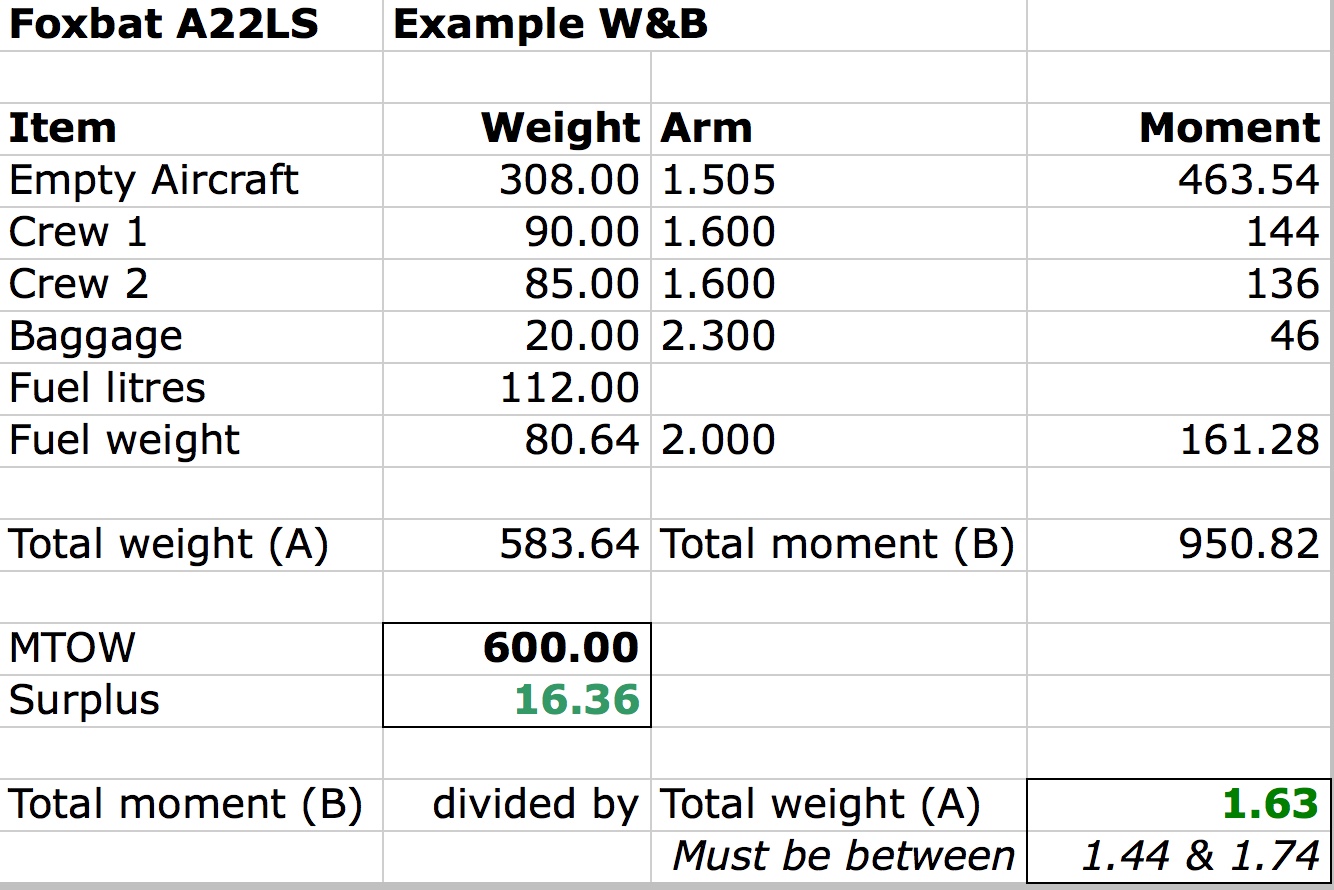

9. Give yourself plenty of time for preflight work – NOTAMs, weather, performance, weight and balance, preflight checks and passenger briefings need to be considered without any time pressures. Avoid in flight decision making challenges by already having in place alternative plans to deal with eventualities such as adverse weather.

10. Consider flying with another pilot. In this way workload can be shared although it will be important that neither of you is ever uncertain as to who is the Pilot In Command at any time.

How might you keep flying safely?

Perhaps the most compelling pointer here is that if you are inclined to fly at all as an elderly pilot then you should either do it frequently or not at all. In most recreational fields the elderly tend to ease off in frequency as their age advances but when it comes to flying it seems that this is quite the wrong approach. I am reminded of an acquaintance, a former WW Spitfire pilot with three operational tours, who wanted to keep driving into his eighties and nineties so he always made sure that he drove at least every other day.

My brother’s keeper

Younger readers may not feel concerned personally with these thoughts just yet but may nonetheless find themselves thinking of some other pilot about whose competence they have doubts. Few of us would have the temerity to approach another pilot in cold blood and suggest that if it is time that they considered retirement but failing to do anything is failing in your duty to that pilot, their potential passengers and to the GA community at large. A better alternative is to discuss the position with other pilots, especially instructors. While an approach by another younger and probably less experienced pilot may be dismissed as insolence a similar approach by several pilots as an agreed body or a CFI would be very difficult to ignore. If you have your doubts about an elderly pilot’s competence you have a duty to perform and you would not want to come to regret having done nothing to prevent a subsequent disaster.

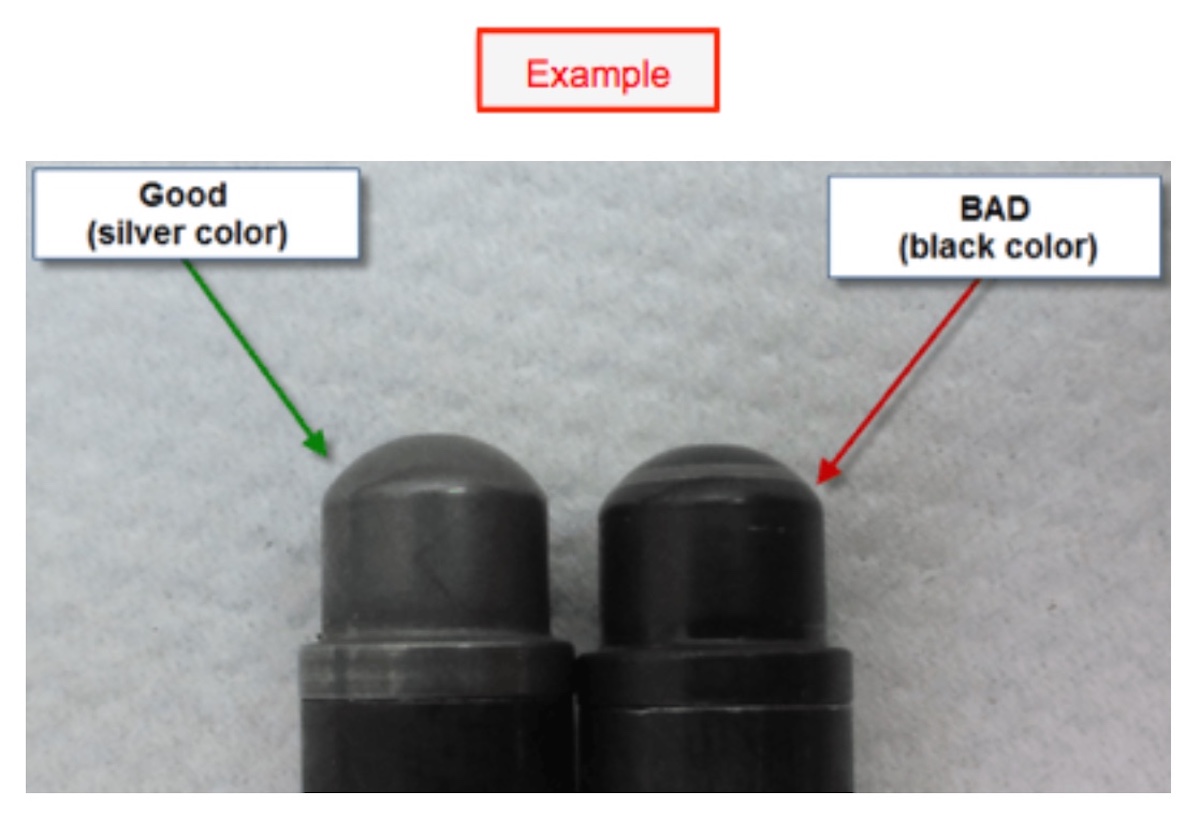

Rotax has issued a new mandatory service bulletin covering their oil filters – SB-912-071.

Rotax has issued a new mandatory service bulletin covering their oil filters – SB-912-071.

Probably the most common comments I get from student pilots – and quite a few experienced pilots too – are about their perceived skills needed to land a light sport/recreational aircraft. In many cases, pilots make comments like: “I pulled back on the controls to flare and the aircraft just ballooned” or “it just seems to float and float along the runway; it just doesn’t want to land”.

Probably the most common comments I get from student pilots – and quite a few experienced pilots too – are about their perceived skills needed to land a light sport/recreational aircraft. In many cases, pilots make comments like: “I pulled back on the controls to flare and the aircraft just ballooned” or “it just seems to float and float along the runway; it just doesn’t want to land”.

…and have a lot of fun, in a few easy steps.

…and have a lot of fun, in a few easy steps.