Looking to buy a new or used Light Sport Aircraft (LSA)? Read on for FoxbatPilot’s exclusive guide on what to look for and how to do it. This might seem a bit of a long read but hopefully you’ll find it useful!

Looking to buy a new or used Light Sport Aircraft (LSA)? Read on for FoxbatPilot’s exclusive guide on what to look for and how to do it. This might seem a bit of a long read but hopefully you’ll find it useful!

1. First and most important, decide your budget!

Like any other major purchase, it’s easy to stray above your limit but decide your budget in the clear light of day and don’t let the red mist of ‘wanting’ overpower the cool breeze of ‘needing’. Write your budget down on your buying checklist to remind you. Big red numbers are best!

Don’t forget that in addition to the aircraft itself, there are plenty of other costs to allow for:

– how will it be delivered/collected? Will that be your cost or the sellers?

– what about insurance?

– where will you keep it when you’ve bought it? At first sight, hangar/shed/ownership/rental may look expensive but aircraft can deteriorate very expensively when left in the Australian open for even moderate amounts of time.

– who will pay for the mandatory pre-purchase condition report and registration transfer?

– don’t forget running costs like servicing, fuel, oil, replacement of worn items like brakes.

– what about essential accessories like headsets and GPS? Are they included, or extras you’ll have to pay for?

2. Take a reality check.

Be realistic – what will you really use this aircraft for? Everyone wants the latest model with all the avionics trimmings but these can be very (very) expensive. If you fly mostly weekends and/or evenings and early mornings, with the occasional longer trip – maybe to an annual fly-in or other event – then save your dollars and get an aircraft that’s simple, less worry, enjoyable and fun to fly. The polish on the shiniest of trinkets can tarnish after even only a short while, so don’t over-equip. Like motor cars, you won’t get back the value of extras like digital screens, autopilots or fancy paint jobs when you come to sell. And more gadgets means higher insurance too. Finally, the more optional items, the more likelihood of something going wrong – aeroplanes are notoriously difficult environments for electronic and other sensitive equipment, even when they are not flying.

3. Get your money lined up before you start looking.

If you are selling an existing aircraft to (help) fund the new one, get it on the market as soon as you can – remember, many printed magazines can take several weeks from deadline to publication. Even online markets can take several days to get going.

If you have the cash in the bank and ready – great! If not, a preliminary application to your bank or finance company will (hopefully) line up the funds so that when you find that gem of your dreams, you’re ready to go. Having the funds ready helps to show the seller that you are a serious buyer. Procrastinating statements like “I need to settle on a property before I can go ahead” or “I need to sell my current aircraft first” might suggest you’re not serious. Worst of all, avoid the “I just have to clear it with my partner/colleague/treasurer” etc, all of which suggest you aren’t really the decision maker, or, worse, are just a tyre-kicker.

4. Start looking.

In Australia, there are several magazines (some are online) with small (and big) ads for new and used aircraft. In particular, for LSAs, try the monthlies – Aviation Trader or Sport Pilot; both are available at newsagents. Also search the internet – you can enter the type of aircraft you’re seeking; alternatively, ‘light sport aircraft for sale’ (maybe followed by your country name) will bring up a host of options. Once you start following the links, you’ll find there is a huge number of organisations selling aircraft. But beware – unless you really know what you’re doing, you should probably avoid buying from overseas. Attractive as the big USA sites are – Barnstormers, Trade-a-Plane, Controller and others – there are many expensive pitfalls when buying and importing an aircraft!

Be thorough in your research; for example look at typical used values for similar aircraft to establish the right price for that model. Search for incident/accident reports to see if there’s any pattern for that aircraft. Talk to other people about your preferred aircraft – but beware, many people have their own favourites (both to love and hate) so listen to everything with a pinch of salt.

5. Go and inspect your selection.

If at all possible, take someone with you – a second pair of eyes is really worth it when it comes to looking at aeroplanes. A suitably qualified engineer is a good choice, even if you have to pick up their expenses.

Before you go flying – patience! – have a thorough look at:

– all the paperwork; are the airframe, engine and propeller logbooks up to date?

– are the serial numbers in the paperwork the same as on the aircraft? Particularly, check the airframe, engine and propeller serial numbers.

– where are the Pilot Operating Manual and Maintenance Manual? Are they the originals? If not, why not?

(It is mandatory for all LSAs to be delivered with a Statement of LSA Compliance, Factory Flight Test Report, Factory Weight and Balance sheet, Pilot Manual, Maintenance Manual and Flight Training Supplement. Without these documents, the aircraft does not technically conform to LSA regulations and may be demoted to ‘Experimental’ status.)

– look for any record of damage repairs and regular service information. If no damage is reported in the books, will the owner give a written guarantee of NDH (no damage history) if you decide to buy?

– check the weight and balance. Aircraft are notoriously willing to put on weight! Ask the owner to guarantee in writing the figures in the aircraft records are correct. If not – will they pay to weigh it?

(Flying an aircraft overweight is probably the most common offence in Light Sport Aircraft. You don’t want to find out through your insurance company when they decline a claim or – worse – through a ramp check, that what you thought was a 325 kilo empty aircraft was in fact a 375 kilo aircraft and you were, for example, 35 kilos overweight.)

– check if there is any significant service work coming up – eg the Rotax 5-yearly rubber, carburettor diaphragm and fuel pump replacement requirement.

– inspect the whole aircraft for damage, leaks, wear, signs of neglect etc. If it’s flown a thousand hours, it’s not going to be perfect but it should still be reasonable for its age and completely airworthy.

– finally, check if the aircraft is on finance, ie: is the owner legally able to sell it?

6. Prepare for the test flight.

Before going for a test flight – let alone deciding to buy, look out for red and amber signals. You’re going to be spending thousands, so make sure you are buying what you want!

Here are some red flags:

– any ‘missing’ paperwork, whatever the reason

– gaps in registration and/or servicing

– owner refuses to warranty the empty weight in writing

– owner refuses to confirm NDH (no damage history) in writing, or details of repairs if carried out (how? by whom? when?)

– unexplained smells, noises, cracks, high wear on a supposed low time aircraft, other defects

– your own gut feeling that something’s not right

Amber signals, where you may be re-assured and/or the issues can be dealt with in the sale price:

– expensive maintenance coming up (eg Rotax 5-year rubber replacement)

– flight hours over about 250 a year (suggests use in flight training)

– only a very limited number of this type of aircraft in the country, which means you may be the flight test dummy!

– more than one owner every couple of years (might indicate problems of one kind or another)

– outstanding loans or other bills on the aircraft (get written information)

In Summary, unless everything is to your satisfaction – WALK AWAY! There will always be another one along soon.

7. Test fly the aircraft.

If you’re flying with the owner, be sure s/he is (a) qualified to fly this aircraft, (b) with you as a ‘passenger’ and (c) is current with medical, BFR etc. Personally, I like to see the licence and flight logbook of anyone I fly with if I have never met them before…In extreme circumstances, your life may even be at stake, so check and double check everything before you fly an unknown aircraft!

The test flight itself could be the subject of a whole book, just on its own. But here are a few pointers:

– will it be easy to exit the aircraft in the event of a problem?

– can you move the controls fully and easily throughout their range?

– does the owner give you stuff like ‘it’s a characteristic of this plane…’ (is that a good or a bad one?) or, ‘I’ll fix that before it’s sold’ (why didn’t they fix it already?)

– listen to the engine and the airframe at every stage – taxiing, engine run up, take-off, climb, cruise, etc etc.

– watch the engine dials, particularly oil pressure and temperature

– can you easily see out while you’re flying? for example, some aircraft have seats which put your eye-line well above the bottom of the high-wing, meaning you’ll really have to duck your head to see out before turning that way.

– watch the owner fly the aircraft before you take the controls. Does s/he inspire you with confidence or blind you with b******t?

– fly for at least an hour; many problems can be hidden for 20-30 minutes

8. Make your decision.

This is important – do not let your heart rule your head! You’ll have a long time to repent a bad decision and it may also cost you big money.

Agree a price with the seller and make it subject to a full and detailed inspection by a qualified engineer – in fact, if the aircraft is registered with RA-Aus, it is a regulatory requirement for registration transfer that a written ‘condition report’ is carried out. Make sure this is done by an independent engineer – ideally someone you know and trust, not one of the seller’s friends.

Whether RA-Aus or GA registered, include a pre-transfer, full 100-hourly/annual service in the deal. This service legally requires all current & applicable service/safety bulletins to be carried out, so you’ll know the aircraft is all present and correct; and if a discrepancy is found later, you’ll have a comeback on the seller. Any problems should be fixed by the seller before you buy the aircraft.

Pay the seller a small deposit to hold the aircraft until you can settle. ‘Small’ means a lot of things…maybe $5,000 is enough to confirm your intent. ‘Until you settle’ shouldn’t mean more than a a week or two.

9. Get your money and insurance finalised.

If you’re taking out a loan to buy the aircraft, it is usually a loan pre-condition that the aircraft is properly insured. As per the very first step – see above – you will already have checked out loans and insurance, so now is the time to finalise them.

A word of caution – depending on the size of the loan and the security you are offering, some finance companies (in particular banks, it seems) require their name to be listed as a part owner on the aircraft title. It is important to clarify this with your loan provider at the outset, as (from experience) I know that this requirement can present last-minute hitches while RA-Aus or CASA reconsider your registration application with an additional name added.

Agree with the seller how you will pay the final amount – some people are OK with bank cheques, some prefer cleared EFT funds before they will handover the aircraft. Cash can be acceptable but tens of thousands in used notes is likely to be both inconvenient and inadvisable!

10. Go and collect your aircraft.

Notice – I say go and collect it. Ideally with a friend for moral support in the event of problems and companionship on the way home. There are a few reasons for this advice:

– if things are not exactly as agreed when you get there, you can turn round and head home if needed. If the seller has flown the aircraft to you, s/he may be unwilling to take it back home if you’re not happy with it.

– you can take it for a final test flight before accepting it. This ensures everything is as it should be; there’s no “It was alright on the way here, I can’t understand how that’s happened” stuff to deal with.

– the flight home is a great opportunity to enjoy your new acquisition and get to know it in all phases of flight. That return trip is likely to be the longest flight you’ll do in the aircraft for a while, as you get to know it.

– particularly if it’s a new aircraft, you’ll be the first person to fly it any distance. Ferry pilots are usually responsible people but you’ll never know if they explored the Vne along the way or ignored the rough air cruise speeds….or had a couple of ‘heavy’ landings.

11. Have fun!

I know the title is ’10 steps to buying a Light Sport Aircraft’ but now you’ve bought it, go out and enjoy it. But take it easy until you have flown at least a hundred hours in it and got to know all its individual characteristics. It may be capable of 130 knots cruise – but that’s no reason to thrash it every flight. It may be able to land and take off from short strips – but not every take off and landing has to be a demonstration of this capability (which almost certainly is greater than yours!). Hopefully, you’ll experience a long and loving relationship – treat your aeroplane right and it will look after you.

This article is intended only as a guide. The opinions are only my own and others may think differently. If there’s anything with which you fundamentally disagree, please tell me directly.

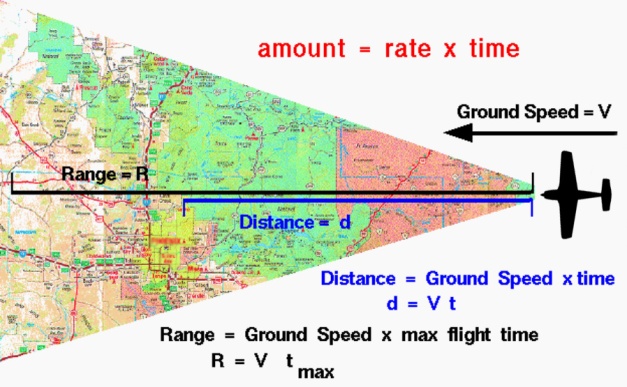

After weight, speed and range are two important aspects of specification to consider.

After weight, speed and range are two important aspects of specification to consider.